We tested how direction from leadership can prevent teams from spinning in circles and create a more purpose-driven organization.

Some say strategy is a framework. Others say it’s a mindset. Most think it’s bullshit you pay a consultant to write. It’s easy to mock pithy mission statements (“it’s just words on a page”) or discount powerpoint decks “sitting on a shelf” but leadership pays dearly to create those words and slides. What if the vision doesn’t land?

We conducted an experiment to answer that question. Building and shaping teams is a big part of management. We wanted to observe if and how strategy could affect the design of an organization.

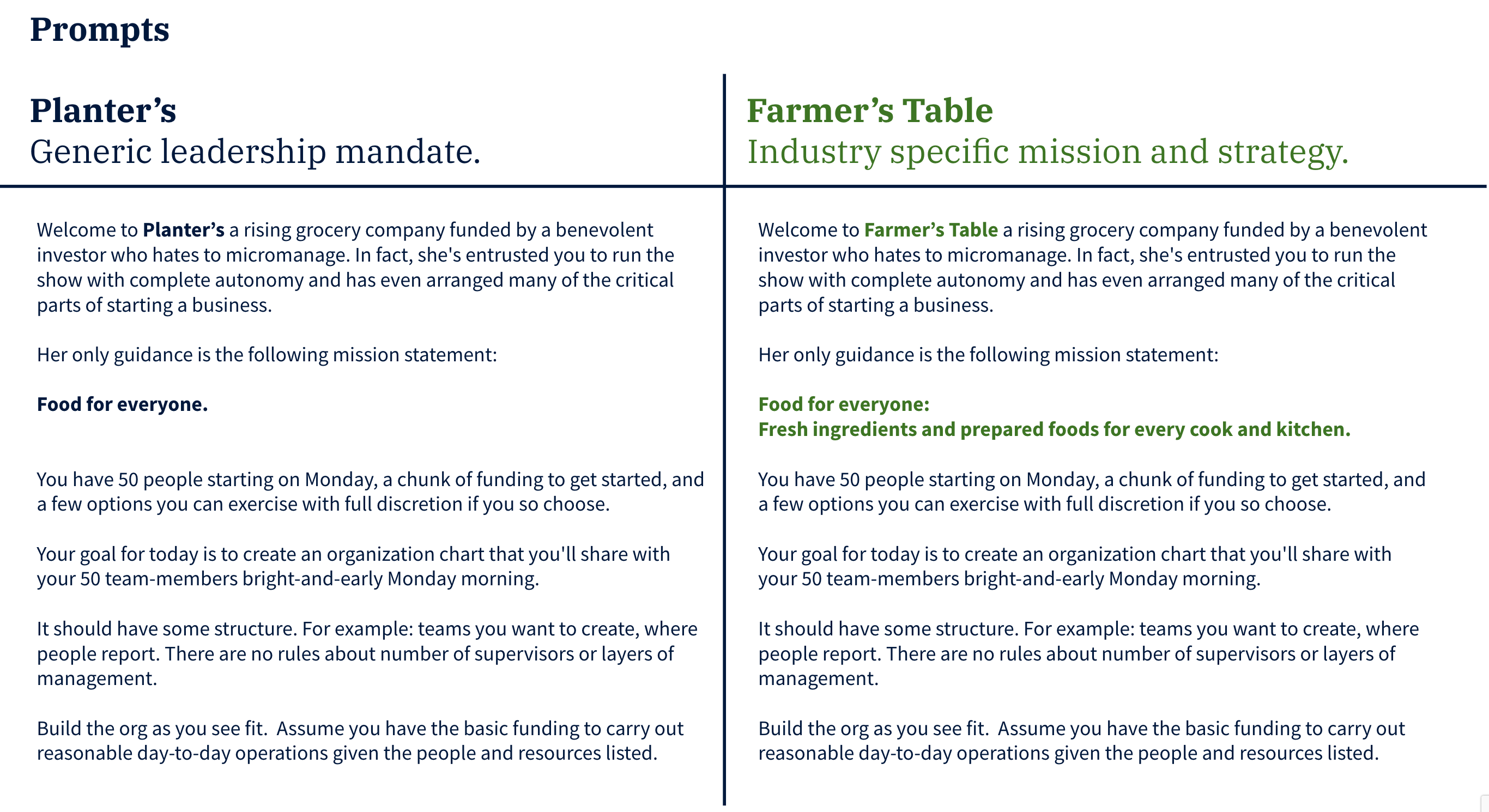

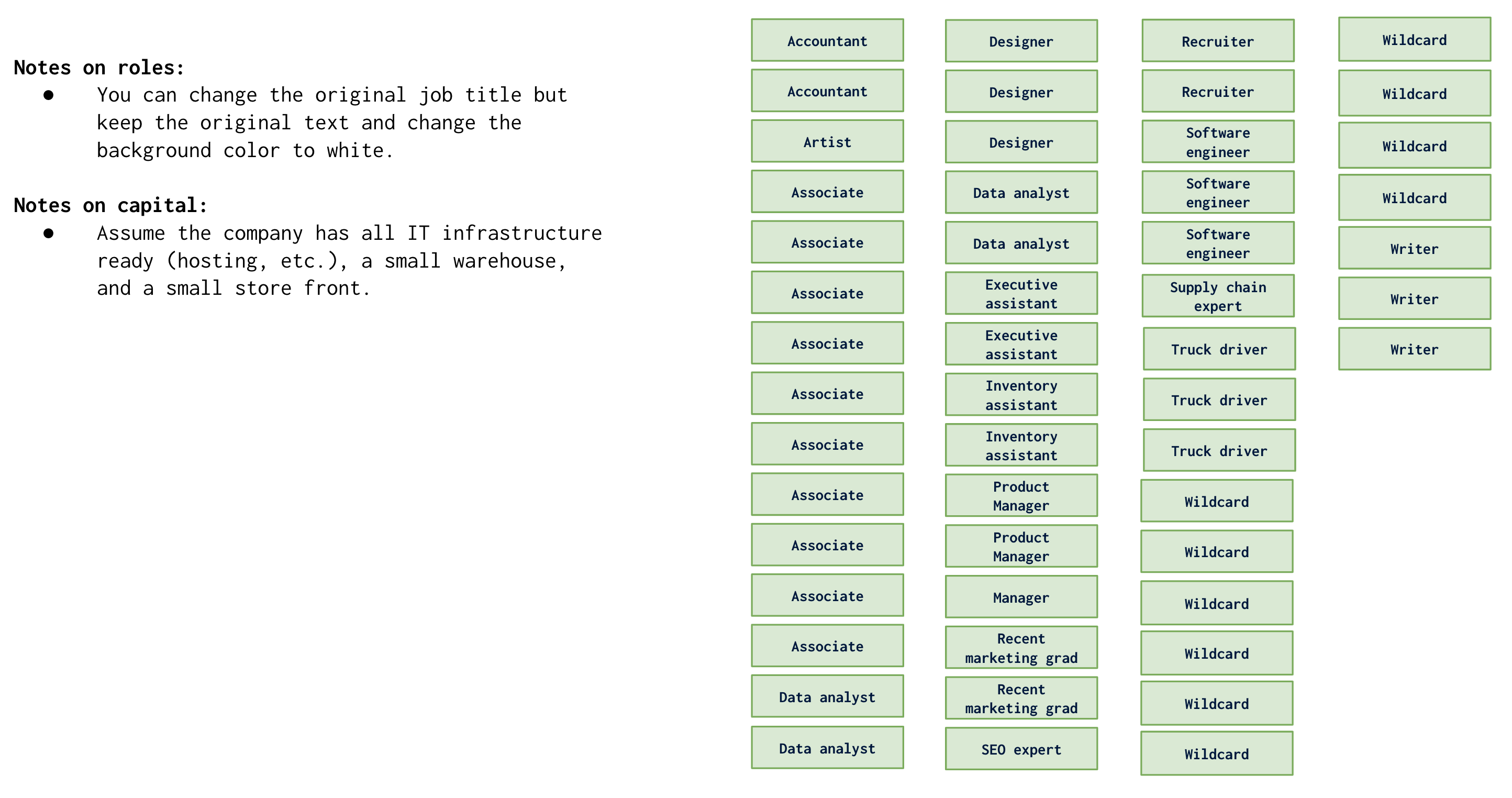

Volunteer participants were split across two groups (a control and treatment) and asked to create an organization chart for a grocery store. Participants were provided with an identical set of predetermined “employee” roles and 10 wildcard options to be arranged into teams at their own discretion. The only twist? A single line in the opening prompt describing the mission statement.

We predicted the additional clarity in the prompt would improve the focus of participants and result in a more specialized and creative organization design. The Farmer’s Table “managers” might be more inspired to consider supply chains, delivery services, catering, or niche cooking services compared to their Planter’s counterparts.1 2

See more on methodology below.

10 words of clarity created dozens of team innovations

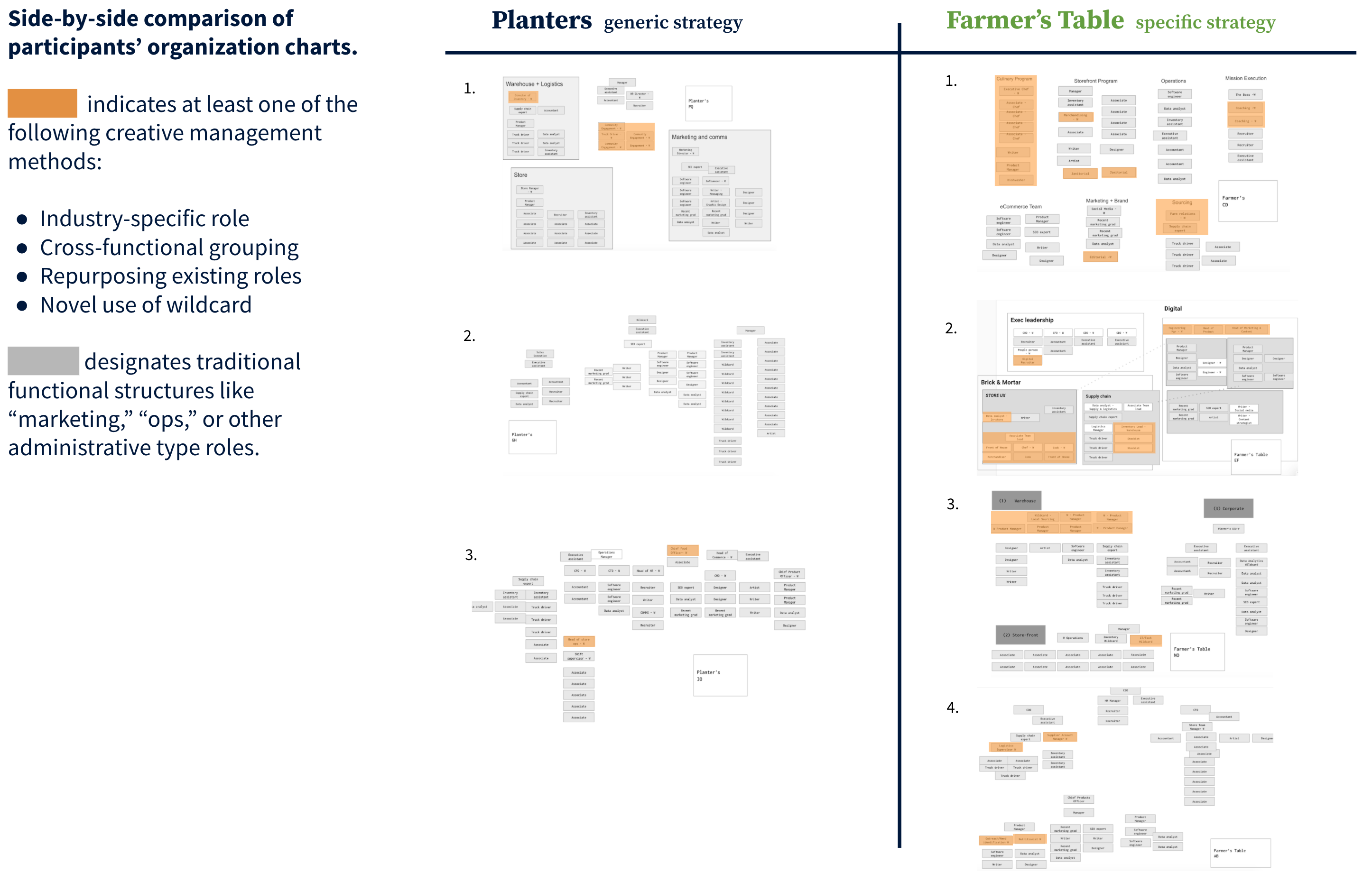

We crunched the numbers after seven sessions and confirmed our hypothesis. Participants with the more specific Farmer’s Table strategy exhibited more creativity in their organization designs than those in the Planter’s cohort.

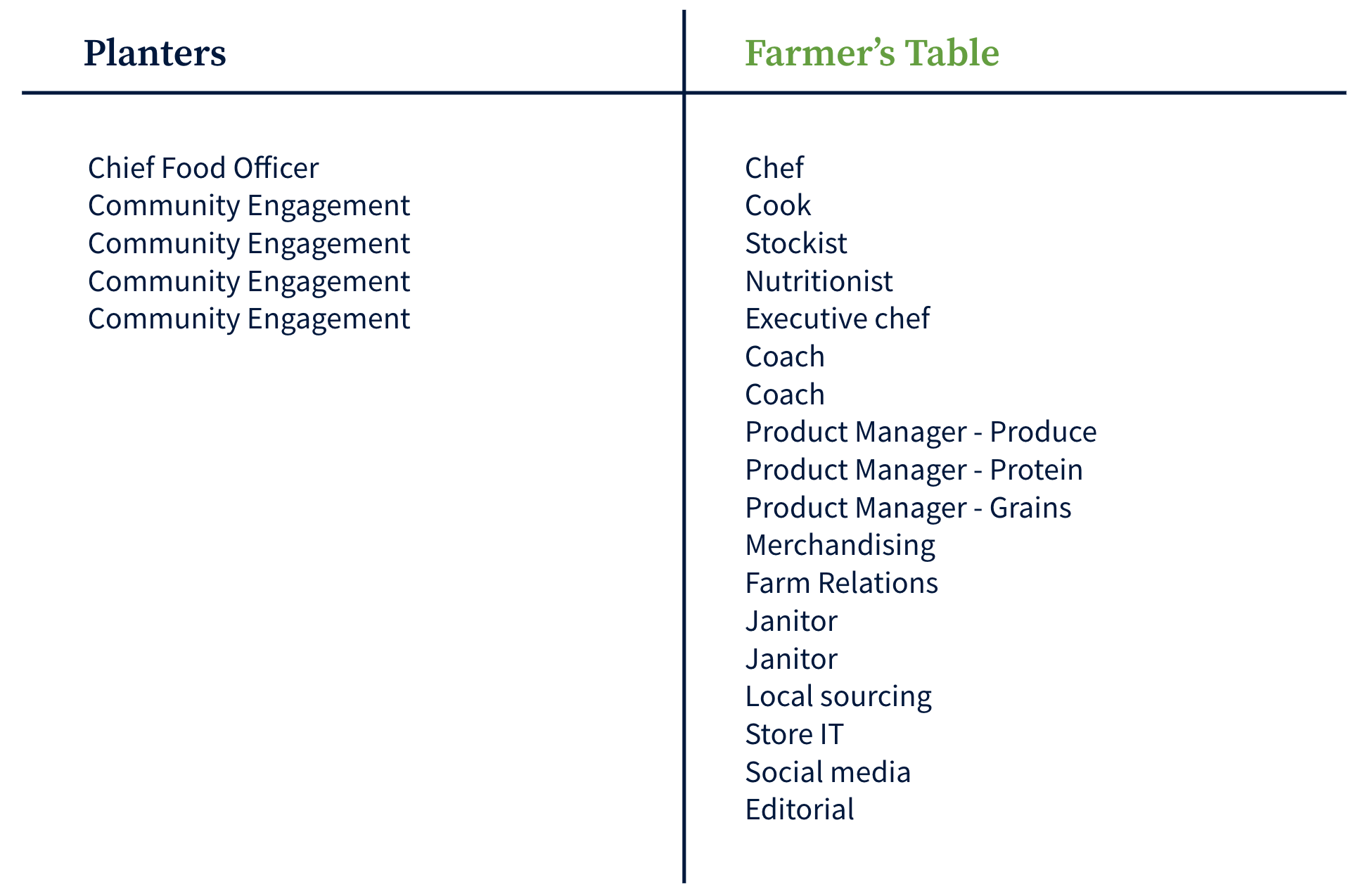

We measured several variables like the degree of cross-functionality, industry-relevant titles and team configurations, and the use of wildcards. A more prescriptive strategy evoked managerial creativity in consistent, meaningful ways. Predetermined roles were often repurposed for specific jobs like meal prep and wildcards were used to provide more context to the operations of the roles critical to the purpose of the organization.

Humans often resort to their known priors rather than inventing something new when faced with a complex set of options. We confirmed that bias in this experiment: participants opted to form a generic organiation design around common functions in the absense of a descriptive, specific strategy. 3

Ambiguous direction led to dry, ambiguous structure.

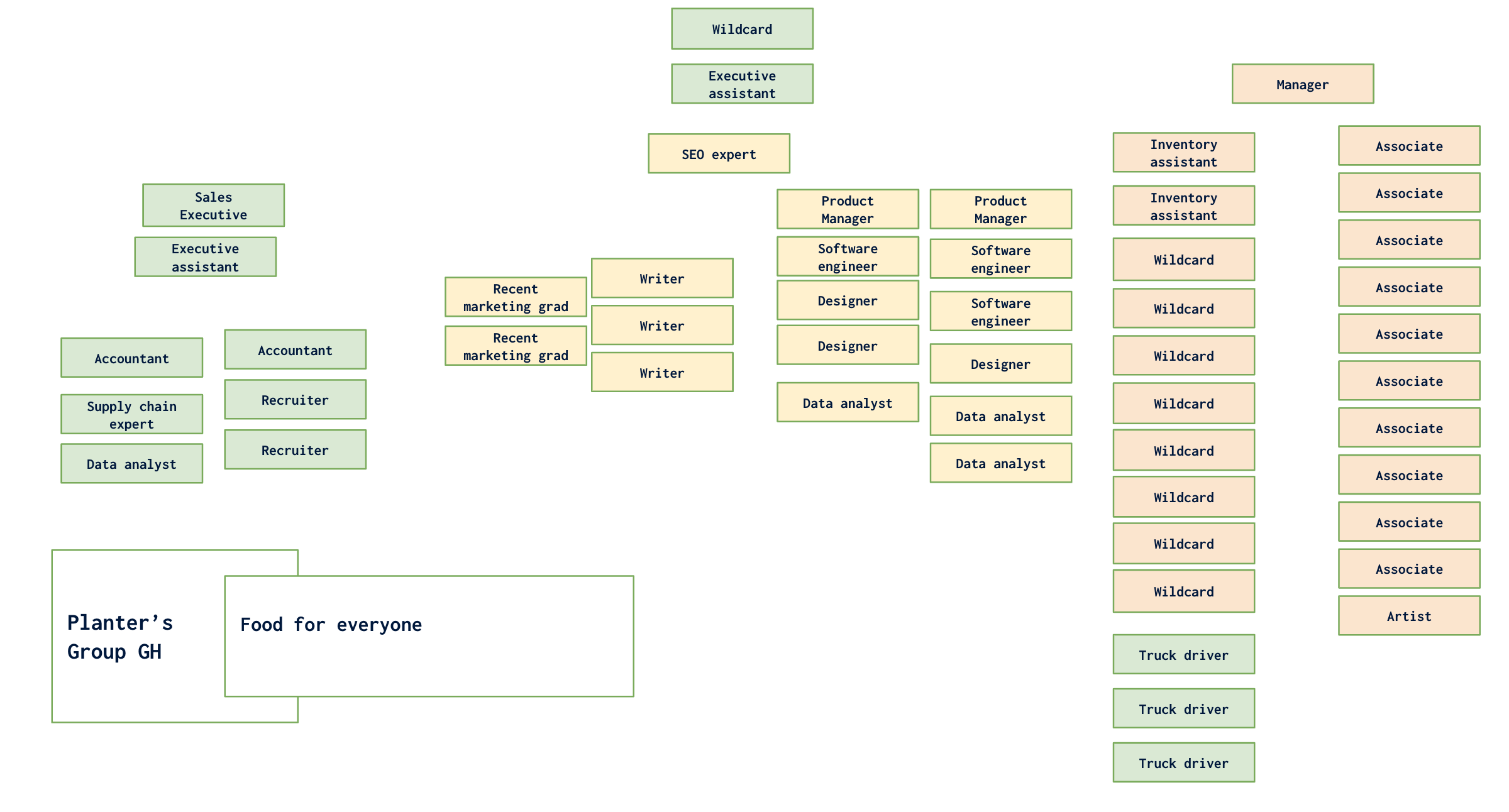

The chart below is a representative sample of the average Planter’s design. Participants in that group often expressed confusion about the open-ended strategy. “Food for everyone…that’s annoying” was a direct quote we heard alongside “should we throw them in with the rest of the designers?” These comments were not a coincidence.

People often default to their known, past experience when faced with hard timelines, many options, and complex choices. For example, if I asked you to name a few job titles, you might say things like “marketer” or “accountant” because those are common words immediately available to you. We saw this defaulting behavior in both groups, but it was more pronounced in Planter’s. The evidence of Planter’s more pronounced defaulting behavior lay in their arrangement of roles and their minimal use of creative latitude as afforded by the wildcards.

“I know we can change titles but it’s just a little unwieldy…I just like the idea of grouping these people together in the same place.”

GH’s chart above is a good example of this bias. In their design, corporate functions are concentrated in one place and marketing is consolidated in two branches. The team under the [store] “Manager” is a large, monolithic structure of associates. All ten wildcards were used to fill a single role under inventory. Altogether, the structure doesn’t break the mold of your basic conception of a grocery store. Teams are not dedicated to any specific purpose outside of their skills affiliation.

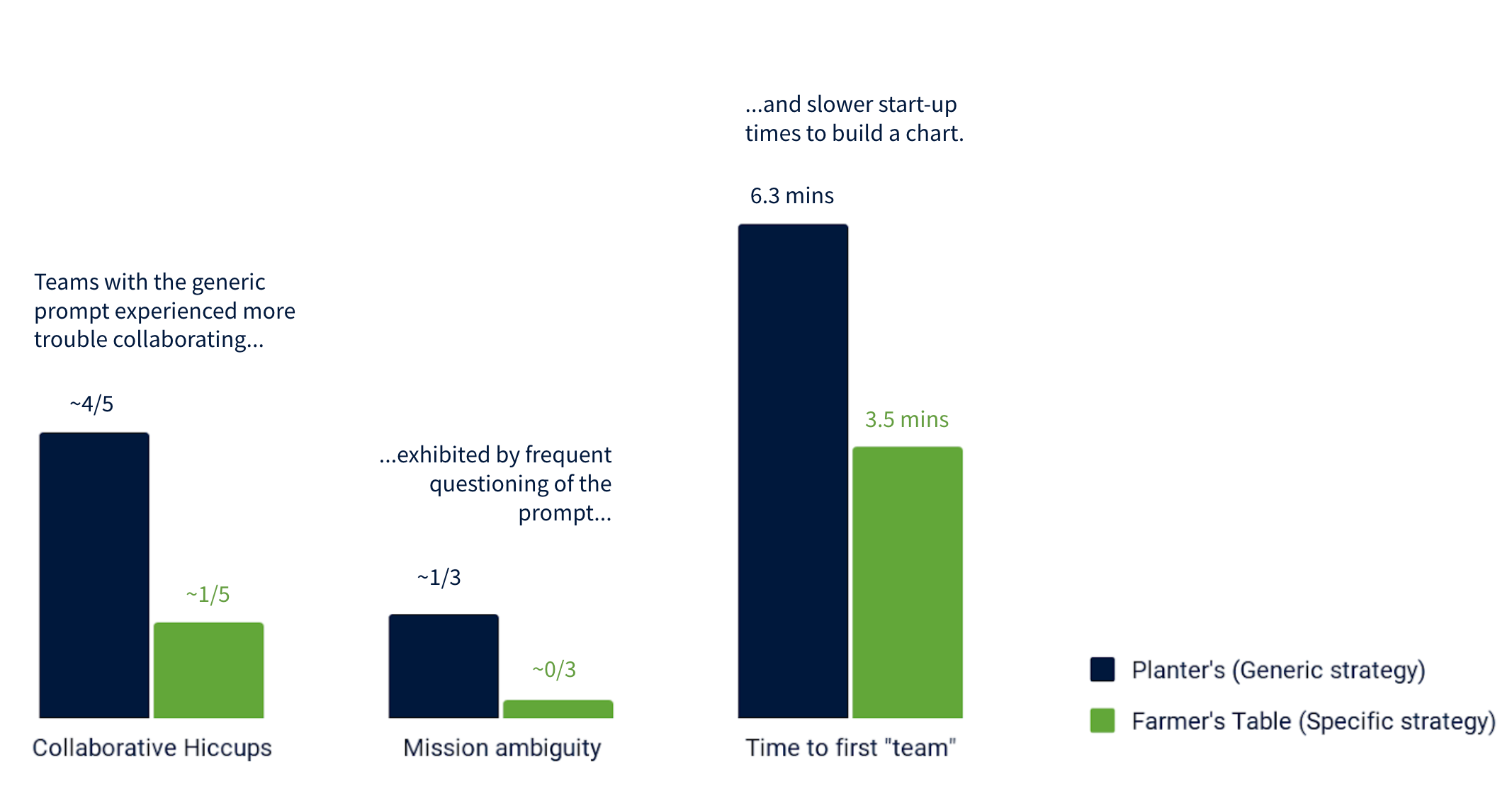

Teams in the Planter’s cohort also found it difficult to rearrange staff and had higher incidents of collaborative friction. Participants would take between 5 and 10 minutes, on average, to start their first branch versus their Farmer’s Table counterparts who would hit the ground running in half the time.

Planter’s mission statement “Food for everyone” did not give enough context or direction to develop strong collaborative flow. The consequence? Generic, administrative organization structures that might pass for a grocery store but leave a lot of creativity on the table.

Specific language clarified the jobs to be done

Farmer’s Table teams experienced an entirely different exercise and outcome. The “ingredients” and “prepared meals” keywords in their prompt told participants that they were expected to cook and maybe deliver. The market segmentation of “every cook and kitchen” hinted that they had to engage a diverse group of customers.

“Maybe we have people who design packaging and work with local farmers to deliver better food.”

“You call us up and you’re like ‘this is what I’m feeling for dinner’ and we get that ready for you.”

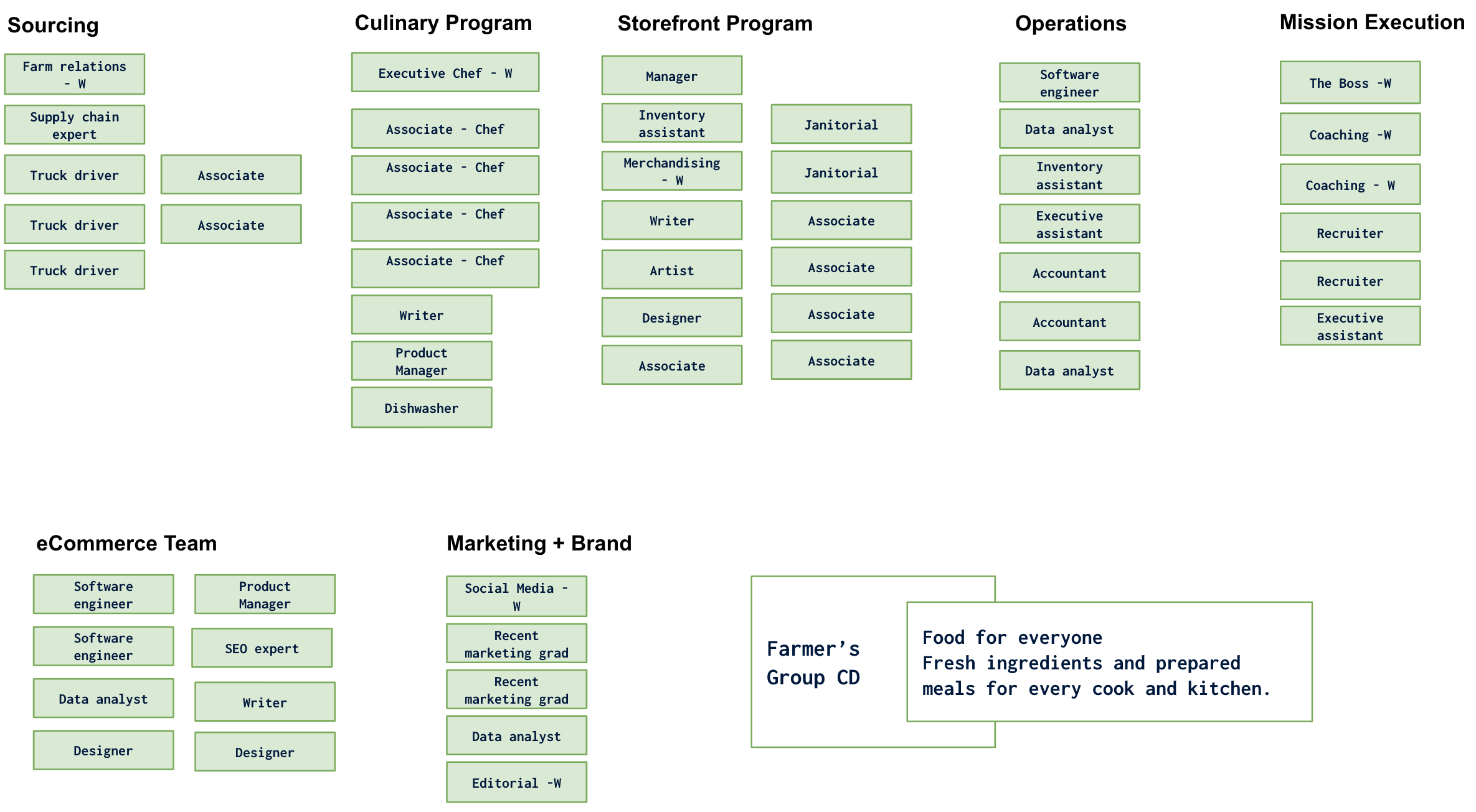

The Farmer’s Table managers imagined how their company would operate in vivid detail. For example, Group CD created a Culinary Program that combined writers, product managers, and several wildcards. A single branch of their organization chart expressed five examples of creative management that we rarely saw on an entire Planter’s diagram.

- Developing a Culinary Program dedicated to preparing incredible meals.

- Using a wildcard to create an Executive Chef role who would lead that team.

- Employing associates (folks described as having summer-job level training) in roles outside the obvious stocking or cashier roles.

- Putting a writer and a product manager together to support customer engagement for the kitchen.

- Using a wildcard to handle the obvious, but overlooked task of cleanup.

Group CD also created Sourcing and Storefront teams that displayed similar managerial creativity. Farm Relations was another novel role in addition to the practical, but necessary Janitorial staff created from the wildcard options.

Other Farmer’s Table teams also ran with this direction. Group AB imagined the store looking like Trader Joe’s and used the designers on staff to decorate signs, as opposed to their sitting in a central corporate office. Another group discussed how they would blend digital with brick and mortar to engage shoppers and enable delivery.

An exercise you can try at home!

Just one sentence changed the course of our experiment. What could a sentence or even a few words do for your entire company? Does your strategy resonate with managers? Does it provide direction while providing space for creativity? It could be the difference between looking like everyone else and building a team with its own take on the world.

You can also duplicate this experiment with your own team using the instructions below. Test a draft mission statement and strategy across two groups and see how your managers build a team. Run it again and again. Building an organization takes practice.

If you want help setting up a workshop like this one or need a review of your firm’s strategy, give us a ring. Schedule some time here or send us a note hello@mccallumpartners.com

A note on methods

Building a realistic picture of management

Each team was given the same exact prompt, set of roles, number of wild-cards, and context surrounding the objective. Time was allowed for clarifying questions, but efforts were made to ensure the similar responses to each type of question.

We introduced several additional controls to mimic real-world scenarios and isolate the effects of our experiment. The first control reflected the inevitability of collaboration. Few executives work in complete isolation. Pairs were constructed to ensure that no one was matched with someone they knew. Attempts were also made to avoid similar career experiences within each pair. Participants were recruited on Twitter and LinkedIn, and thus limited to the network of the author. Future research should cast a wider net to obtain a more representative sample.

Second, the exercise incorporated the requirement of time-sensitivity at work. We gave participants roughly 30 minutes to arrange the roles into something resembling an organization chart.

Third, we intentionally flooded participants with information. We presented each group with a story of the firm, a list of 40 predetermined roles, 10 wildcard options, and several rules regarding formatting and objectives. A small organization of 50 people groups into teams of 5 has over 2 million possible configurations. Managers face complex choices on a daily basis that push them into making sacrifices and expose their underlying biases. We wanted to trigger a state of “bounded rationality” in each group to observe whether the prompts had an effect of easing and guiding their design of the organization.

Team incumbency was the last major theme. With the exception of a true start-up, managers join organizations with existing employees. The 40 predetermined roles ranged from accountants and recruiters to inventory assistants and designers. The titles were industry-agnostic and did not reference a specific company. We wanted to observe if the prompt treatment would inspire managers to give new meaning to a generic list of job descriptions.4

Taking it a step further, we created wildcards. Managers were given 10 empty boxes that could be filled with any role or person they could imagine. If you wanted Oprah on your team, we allowed Oprah. The freedom presented by these empty boxes opened another window for creativity. We wanted to see whether this prompt would impact how managers used that latitude.

Footnotes

-

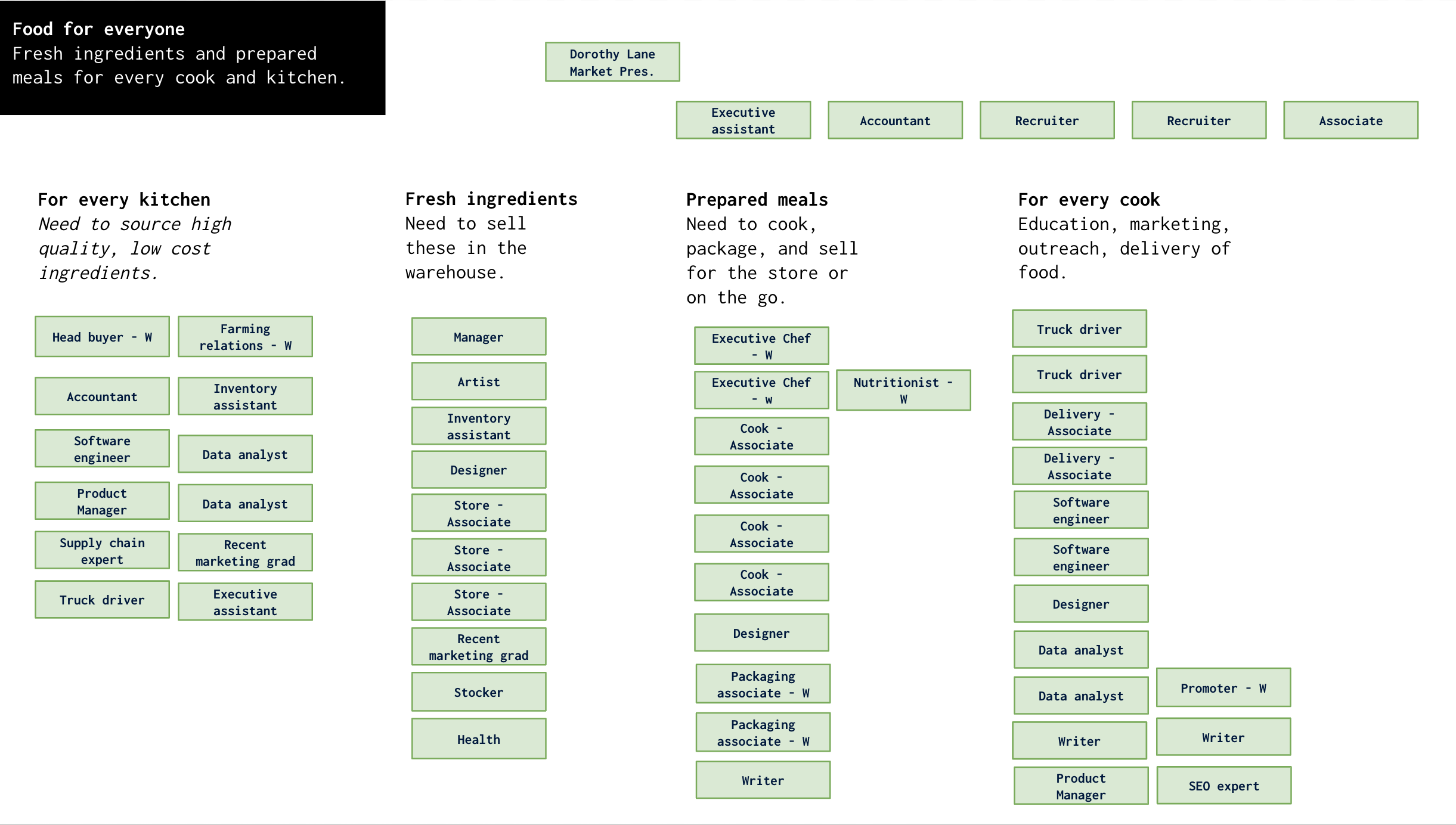

Example of an anticipated organization chart for Farmer’s Table (specific strategy). We anticipated Farmer’s Table teams to use wildcards for specialized roles like Chefs, Nutritionists, Promoters, and Farming Relations, and repurpose existing roles like Associates for specialized purposes like Delivery and Meal Prep.

-

Business historian Alfred Chandler defined strategy as something that informs the design of an organization. The size, shape, and composition of teams are a product of management’s vision for the company. Our experiment used his theorem as the backbone for developing our hypothesis and the results confirmed the timeless observation.

Chandler, Alfred Dupont. Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. United States, Beard Books, 2003.

Chandler Jr., Alfred D.. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. United Kingdom, Harvard University Press, 1977. ↩

-

Herbert Simon challenged the prevailing notion in economics that consumers, managers, or investors were perfectly rational. Simon thought this assumption went too far. How could an investor simultaneously compare put options amongst thousands of different assets? How could anyone possibly grasp the full complexity of a 1,000+ employee operation with offices spread across the globe? The academic and theoretical expectations of what the average person could optimize exceeded what he saw in reality.

Bounded rationality suggests our ability to make good decisions is limited by: 1. The information before us. 2. Our mental ability to process and evaluate that data. 3. And the time we have to mull it over.

Our experiment triggered each of those factors. Participants were time limited, flooded with many roles and instructions, but also forced to create certainty and direction where none excited.

Simon suggested that we satisfice in these cases to deal with our human limits. Individuals create simpler models of reality to process information and evaluate their options. The term is a portmanteau of satisfy and suffice – people find a satisfactory solution that meets a minimal need to compensate for our human limits.

Example: You write a shopping list and a budget to simplify your needs at the grocery store rather than parsing through thousands of individual CIKs. You could spend ten hours in the store looking at each ingredient to get inspired searching for the perfect recipe, but you don’t.

Bounded rationality and satisficing behavior are often subconscious and thus influenced by your experiences, position, and motivations. The implications for management are enormous. What are the limits of someone’s ability to grasp the full scale of potential on their team? Where do personal perspectives create divergence from the norm? Are there models that managers use more commonly than others? Are those generalized models useful or suboptimal? What makes it easier to identify a clear structure and operating model?

Simon, Herbert Alexander. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-making Processes in Administrative Organization. United Kingdom, Free Press, 1976. ↩

-

Edith Penrose called this the “resource based view” (RBV) in her 1959 seminal book The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. She defined an organization as a pool of skills, knowledge, and tools directed toward a common purpose. The conclusion is straightforward. Managers exist to coordinate those people and tools around a common purpose. Thus, the growth of any firm is promoted (or constrained) by managerial competency, that is, the ability for managers to see the latent potential in all the individuals, the various combinations of skills, knowledge, and technologies, and apply those capabilities toward unique, novel, innovative, productive uses.

The framing is elegant and the possibilities are endless. Who’s to say we couldn’t pair a videographer with an accountant to share financial information in a more effective medium for investors? What if software developers were paid bonuses for user-testing their products with a representative sample of the country? Penrose believed management is creative work that continually seeks to maximize the potential of employees to achieve greater results in the market.

Penrose, Edith, and Penrose, Edith Tilton. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2009. ↩